Embrace Your Belonging

How the Eastern Oyster challenges me to be a better human member of the web of life.

I sat down to write about June a few weeks ago. As usual, at this time of the year, my thoughts turned to abundance. What is abundance? How do I see abundance? Where do I see abundance? What does the OED say? And, there it was.

An overflowing quantity or amount (of something); a large quantity; plenty.

Plenty. My thoughts turned to last year’s June post, When Plenty is Too Much. Last year I concluded that plenty is not having what we need without over reaching. Plenty is more than enough, a great deal.

My Friend, the Oyster

Thinking about abundance and plenty led me to thinking about the Chesapeake Bay Oyster, the Eastern Oyster. That may seem like a big leap to some. To me, the Eastern Oyster is an old friend. Okay, so the Oyster is not a friend to cuddle up with. After all, the shell is made of calcium carbonate, there’s nothing snugly about that. The Oyster is a friend to whom you can tell your deepest secrets. When the Oyster closes its shell, it holds its secrets tight and impenetrable. No secret escapes. In fact, when they are stressed out, they shut their shells, nice and tight, and try to tune out the stress around them. It’s a protection tactic. The Oyster is hard to pry open, if you’re inclined to do so. Most importantly, as any good friend does, the Oyster challenges me to be a better human.

I have food memories of the Oyster. Oyster stew on Thanksgiving. Raw oysters, only in months with an R. (Biology and food safety concerns contributed to this adage). Memories of hearing stories about the abundance of Oysters in the Bay —giant sized oysters, Oyster Wars, Oyster pirates, and a town on the Eastern Shore built on Oyster shells. These stories were from a time when there truly was a remarkable abundance of Oysters.

It wasn’t until I moved to the tiny town of Tylerton on Smith Island to work for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation in their education program, that I learned how important the oyster is to my well-being and the existence of the Chesapeake bay ecosystem. Oysters are important, simply because the Oyster exists.

Smith Island - The last inhabited off-shore island in the Chesapeake Bay.

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in North America. It’s enormous, 200 miles long and an average of 12 miles wide. But, it has only one remaining inhabited island, not connected to land by a bridge, accessible only by boat. Smith Island. The small islands that make up Smith Island have been waypoints and safe harbors since the days of the Chesapeake’s First Peoples, the Native Americans. Pirates, colonists, watermen, and farmers have washed up on their shores at different times.

Smith Island was chartered by Captain John Smith in 1608 and the first European inhabitants were recorded on the island in 1657. Smith Island is actually three towns: Tylerton, Rhodes Point, and Ewell. Ewell and Rhodes Point are connected by a road. Tylerton is on its own island. Tylerton had about 75 residents when I moved out there in 1989, and that number is lower now. The family names from 1657 are the same names still on the island. They have their own dialect. The waterfront is dotted with crab shanties and docks. The main institution is the church. Mail is delivered by boat. It was a big deal when Smith Island had to get house numbers around 1990 to facilitate 911 dispatch and other emergency services. After all, everyone knew who lived in every house.

The islanders way of life has always been exclusively tied to harvesting the aquatic life in the Bay. Crabs in the warm months; Oysters in the cold months. When I moved out to Smith Island in 1989, the Oyster population was at an historic low. The population decline began in the late 1800s and by 1989 there was only 1% of historic levels of Oysters left in the Bay.

The call for an Oyster moratorium.

Tom Horton, an environmental writer, and Bill Goldsborough, a fisheries scientist also worked for the Chespaeake Bay Foundation (CBF). Tom and Bill, are deeply committed to the environment, and passionate about the Bay. They are also very comfortable with difficult conversations.

In 1991, CBF commissioned Tom to write a book on the state of the Bay entitled, Turning the Tide: Saving the Chesapeake Bay. In it, he called for a three year Oyster harvest moratorium, the average time it takes an Oyster to mature. CBF pushed forward the agenda.

CBF opened an experiential education center on Smith Island in 1978. Bill was the first manager of the CBF center. Tom came in the mid-1980s. And, I came in 1989. There was thirteen years of history and community before the suggestion of a moratorium in 1991. The islanders and the CBF educators who worked and lived on the island had built strong, friendly, and supportive relationships.

I remember how the islanders felt after CBF raised the idea of an Oyster harvest moratorium. Their anger was real. So was their disbelief. There were angry signs posted on the island. They were worried about their livelihoods and their families. I remember one islander saying, “We’re not angry at you. It’s the bay foundation.”

The moratorium did not come to pass.

What did happen, is that an important dialogue opened up about the importance of Oysters to the Bay. The members of the Maryland Waterman’s Association wrote commentaries in the local newspapers. As did scientists, elected officials, and community members.

Oyster management moved away from only supporting harvest, to:

creating sanctuaries that were permanently closed to oyster harvest and protected by law.

rebuilding public Oyster reefs.

supporting shellfish aquaculture (Oyster farming).

recycling Oyster shell from restaurants and other businesses to rebuild Oyster reefs.

planting wild Oyster seed, substrate, and spat-on-shell on Maryland's wild harvest reefs.

community members volunteering to grow Oysters in 30+ Chesapeake and coastal Bay tributaries.

And, it has made a difference. The Oyster population has tripled in the last 20 years, according to the 2024 Benchmark Oyster Stock Assessment by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. From 2.4 billion adult oysters in 2005 to over 12 billion oysters, 7.6 billion adult oysters and over 5 billion juvenile oysters in 2024

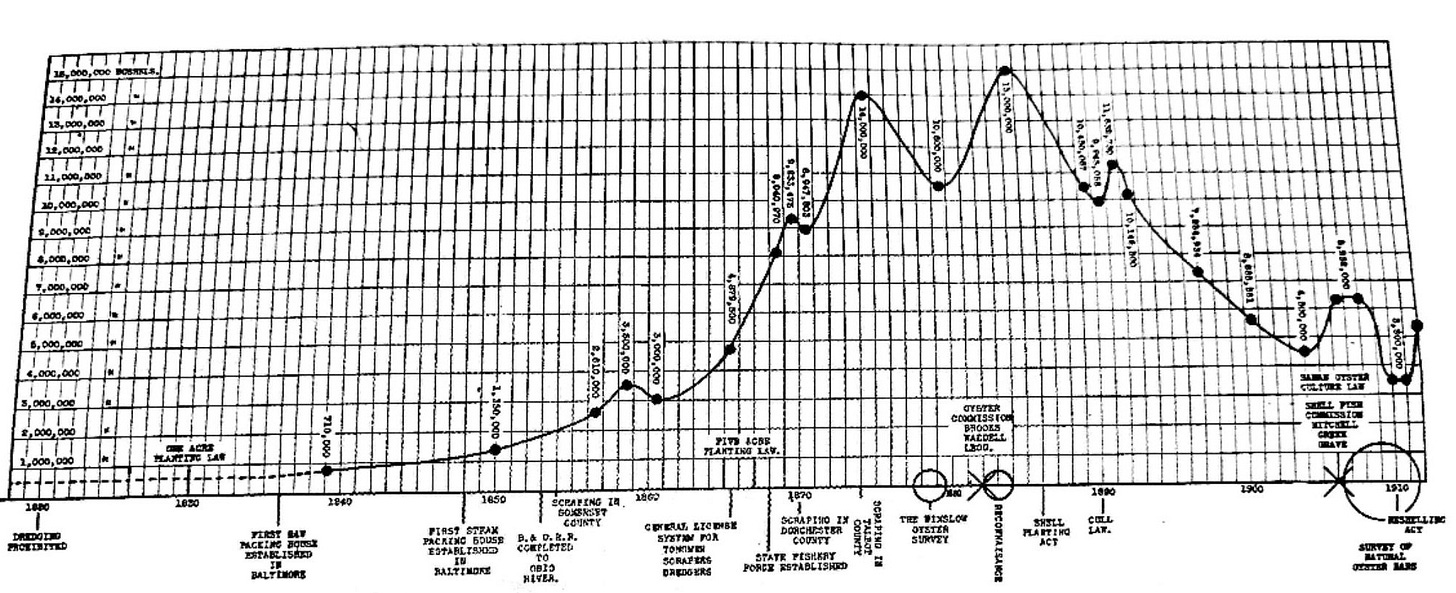

Is that enough? Is that plenty? When compared to the harvests of the 1880-1906 — where harvests were between 6 million and 15 million bushels each year — it certainly doesn’t seem like enough or plenty. (See chart below). It does, however, seem to be moving in a positive direction. Clearly, there is more to be done.

Oysters are important, simply because they exist.

When most people think of Oysters, I suspect they first think of Oysters as food. Then, they think of the work of harvesting Oysters. But Oysters are so much more than a livelihood and sustenance for humans.

Oysters are a keystone species (a critical component) for the entire Chesapeake Bay ecosystem. They’ve been around for approximately 15 million years. The old timers say that when Captain John Smith first came up the Bay, the Oysters were so plentiful that they stuck out of the water and cleaned the water in the Bay in a day.

The Eastern Oyster is a bivalve so it has two shells. The soft body of the oyster is on the inside, and when it senses danger it shuts the two shells to protect itself. The shells are teardrop shape, rough, and made of thick layers of calcium carbonate.

William Strachey, early English settler and writer, visited the Bay in 1612, and said, "Oysters there be in whole banks and beds, and those of the best. I have seen some thirteen inches long.” (The Oyster in Chesapeake History by Henry M. Miller.)

Swiss traveler Francis Michel in 1702 said: “The abundance of oysters is incredible. There are whole banks of them so that the ships must avoid them. A sloop, which was to land us at Kingscreek, struck an oyster bed, where we had to wait about two hours for the tide. They surpass those in England by far in size, indeed they are four times as large. I often cut them in two, before I could put them into my mouth.” (Report of the Journey of Francis Louis Michel from Berne, Switzerland, to Virginia, October 2, 1701-December 1, 1702)

When Europeans like Strachey and Michel first saw the Bay, they looked at it through the context of their own experience. The Bay was so different from where they came from. Were their statements hyperbolic? May be.

It’s hard to know how many Oysters were in the Bay when Strachey and Michel made their observations. What we do know is that the Bay was a stable, mature ecosystem at the time. We also have first hand accounts such as theirs and later harvest data to compare. The chart below are Oysters harvested in millions of bushels from 1839 to 1912.

The highest harvest was in 1885 —15 million bushels. In 1892, 11,633,000 bushels were harvested in Maryland, and 5,985,0000 in Virginia. There was what seemed to be a limitless abundance of Oysters.

Disease, over-harvesting, habitat loss, and pollution have left the population resembling nothing close to what Strachey and Michel described. Today, although an adult Oyster can grow to about 8 inches, 3 to 5 inches is more typical. A legally harvested Oyster must be three inches from hinge to bill, along the longest part of the shell.

Now, the Oysters have to contend with climate change.

Oysters and Climate Change

There are three very important pieces to understanding Oysters and climate change:

They like salty water.

They are filter feeders.

They build bars or reefs.

Oysters prefer brackish and salty water. Their optimum salinity (salt) range is 10ppt (parts per thousand) to 28ppt. That means that for every 1000 grams of Bay water, between 10 and 28 grams are salt. For context, the average salinity of ocean water is between 34ppt and 36ppt and freshwater is less than 1ppt. If there are extended periods in the Bay where the salinity is under 5ppt, there is significant mortality to Oysters.

Oysters are filter feeders. They pump water through their gills, trapping particles of food, nutrients, suspended sediments, and other contaminants. This helps keep the water clean. It also ensures the necessary conditions for underwater grasses and other aquatic life to thrive. It is said that, under the right conditions, one Oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water in a single day.

Oysters spawn in early summer when water temperatures and salinity levels rise. They like water temperatures between 68°F and 86°F and salinity of 10ppt for spawning to commence. Adults release eggs and sperm into the water. In less than 24 hours, fertilized eggs develop into free-swimming larvae. Over the next two to three weeks, Oyster larvae are planktonic (drifting, free flowing through water). They eventually reach a point where they can attach to hard substrate, especially other Oysters. Once larvae attach, they are called “spat” and they are on their way to becoming a recognizable Oyster. This is also how Oyster bars or reefs are formed — one layer of Oysters on top of the other.

I use bar and reef interchangeably — bar because that is what comes naturally to me, and reef when I want to ensure added clarity. I suspect the prevalence of using “reef” is to provide people with a visual they may already be familiar with. I also suspect it is because saying, “They build Oyster bars” could be misconstrued. After all a popular magazine ran an article in 2022, entitled: America's Best Oyster Bars: A guide to the best oyster restaurants from coast to coast. Um, that’s not the kind of Oyster bar I’m discussing here.

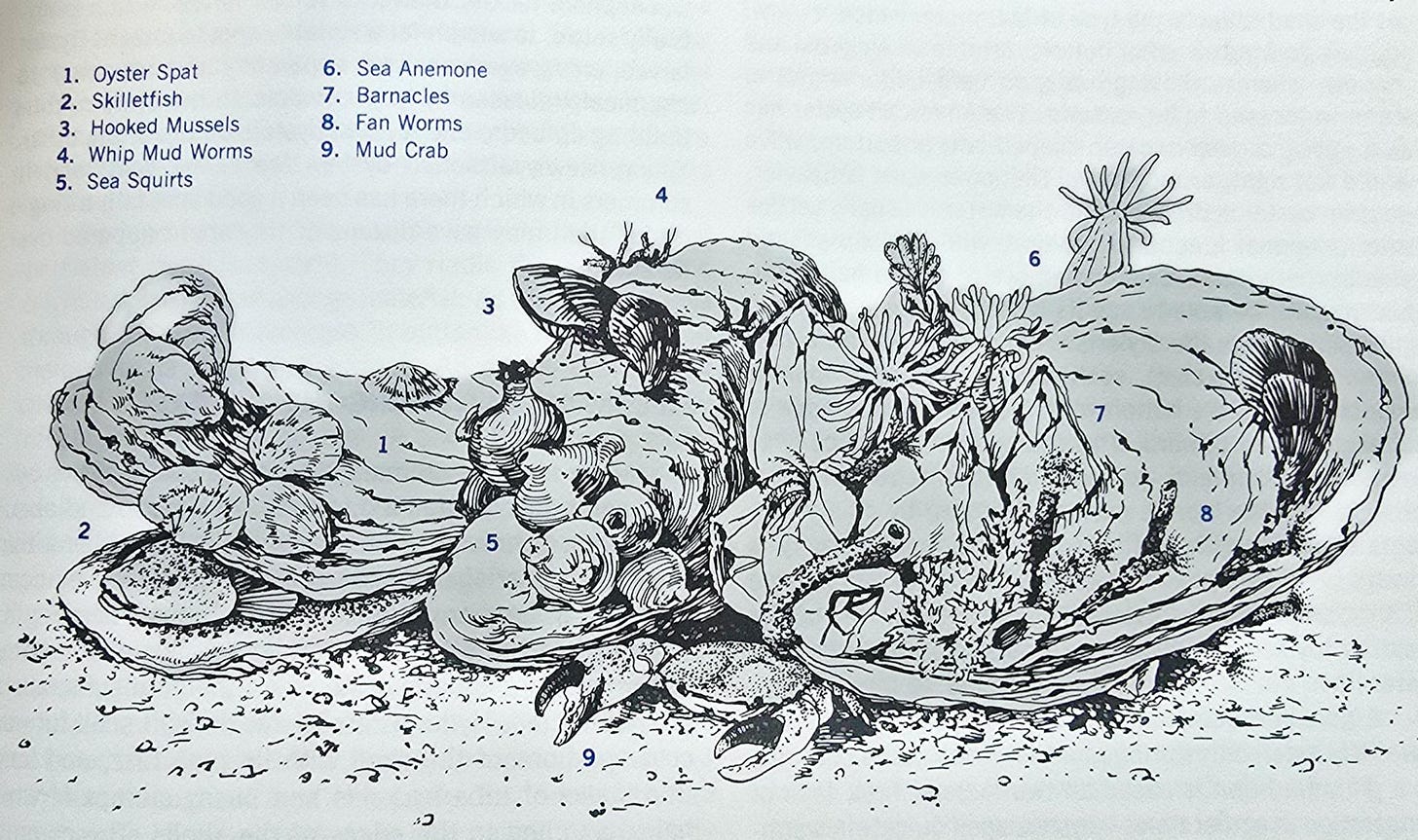

So, Oysters build reefs or bars. The hard surface of Oyster shells and the nooks between the shells provide places for all sorts of marine life. Some of the animals live on the Oyster shells, some attach to the shells, some live in the shell itself. Worms, sponges, and mud crabs are plentiful. Grass shrimp, amphipods, bryozoans, anemones, barnacles, oyster drills, hooked mussels, and red beard sponge. Many of these serve as food for larger animals including striped bass, weakfish, black drum, croakers, and blue crabs.

Then there are residents who move about the Oyster bar. The Oyster Toadfish. The Gobies, Blennies, and Skilletfish. The juvenile fish looking for food and hiding places.

There is a bevy of life within the Oyster bar community. Young are born. Lives are lived. Communities are built. Death continues the cycle. It’s all interdependent.

Only an abundance of oysters in the Bay will do.

Climate change is expected to alter the volume and intensity of precipitation in the coming years.

Take a look at the month of May. Our average monthly precipitation total in inches for May is 4.3. This year, May 2025, the precipitation total was 6.53. That’s 2.23 inches above the average. 152% above the average. Now that it is June, precipitation historically drops down to 3.7 . We’ll see what this month brings. (Maryland Department of the Environment).

We already have more intense downpours and longer dry periods between rain events. Combine increased precipitation with rising sea levels and warmer temperatures, and the Chesapeake Bay’s ecology is dramatically impacted.

All of that fresh water drops the salinity. The brackish nursery and home that the Bay provides for so many species fundamentally changes with large infusions of fresh water.

When the salinity drops, Oysters can’t move to find a better location. Lower salinity may reduce the prevalence of diseases and parasites that affect their health. But lower salinity also affect their ability to reproduce. And, extended periods of salinity under 5ppt, means death. Fewer Oysters, less filtering, more habitat loss.

Sea nettles also prefer this brackish Bay water. Lower salinity means less sea nettles. Sea nettles eat zooplankton, fish larvae, and comb jellies--which in turn eat Oyster larvae. It’s a delicate balance. Fewer sea nettles, more zooplankton, fish larvae, and comb jellies, fewer Oyster larvae, fewer Oysters, less filtering, more habitat loss.

Without Oysters:

Excess nutrients (nitrogen, and phosphorus) fuel the growth of algae blooms.

Algae blooms create low-oxygen “dead zones.”

Increased turbidity.

Light cannot penetrate the water to reach the submerged aquatic vegetation (bay grasses).

Submerged aquatic vegetation dies due to low oxygen.

Sediment suffocates aquatic life.

Oyster bars are not available to provide habitat for other species.

Stress related to poor water quality and habitat loss may lead to disease for other species.

On top of all of that, without Oyster reefs:

Wave energy would not be absorbed.

More sediment, nitrogen, and phosphorus run off.

Increased turbidity and all of the results that follow (listed above).

Loss of shoreline ecosystems such as marshes and bay beaches.

Stress related to poor water quality and habitat loss may lead to disease for Bay species.

I don’t want to imagine what life without the Oyster looks like. Yet, it’s important to imagine what it looks like, what it smells like, even what it feels like to the species that have called it home for millions of years. Dark water. Devoid of most life.

When it comes to the Eastern Oyster, having enough, a sufficient amount, isn’t good enough. Plenty is not enough, either. Only an abundance of Oysters in the Bay will do. An overflowing quantity.

Oysters are not the solution to the Bay’s problem, but the solution won’t come without them.

The truth is, it comes down to us, humans. We need to be better humans. And, we need to be better partners with our ecosystem community. I am not a part from the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem. I am a part of this ecosystem. We humans do nothing in isolation. Our lives and well-being are inextricably tied to the lives and well-being of the entire ecosystem where we are planted, to all of the species that are a part of it. We know that intellectually. We, humans, need to start acting like we believe that.

As Glennie Kindred says in Between the Worlds, “Sit with the natural beauty of the world, inviting connection….slow the pace, and reach for inclusion…Embrace your sense of belonging.”

Where we turn our attention, our focus follows. Let’s turn our attention to reclaiming our deeper connection to this magnificent Earth. Let’s draw strength and guidance from the Earth and the web of life. Let’s turn our attention to regenerative actions that support the health and well-being of the interconnected natural world and our human communities. Let’s find a way to live differently. To work differently. To house ourselves differently. To travel differently. To use energy differently. To eat differently. To live more lightly. To be better human members of the web of life.

Where is abundance needed in the ecosystem in which your feet are planted?

5 Notes

Five final notes on what I’m doing, listening to, making, and practicing in yoga.

Doing: This month, when the rains stop, and the sun begins to shine again, my meditation practice moves outside. I have a dedicated space with a comfortable Adirondack chair surrounded by beautiful plants.

I have a focal point that is composed of stacked rocks with two shells at the top: an Eastern Oyster shell and a Gryphaea shell. Rocks in the stack all contain tourmaline which is said to support protection and the dispelling of negative energies. The two shells at the top are what make the stack unique.

The first shell is the Eastern Oyster shell. This shell comes from the Chesapeake Bay. As discussed above, the Eastern Oyster is a keystone species in the Chesapeake Bay. The Eastern Oyster’s survival is critical to the survival of the Bay and all of its inhabitants. This Eastern Oyster shell connects to ancestry, change, place.

The shell at the very top of the stack is the Gryphaea shell. Gryphaea is a genus of Oyster that went extinct about 34 million years ago. The Gryphaea shells that interest me the most come from Dix Pit near the village of Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire, England. Dix Pit is one of the largest and most-remarkable Pleistocene assemblages of more than 1500 vertebrate fossils spanning over 200,0000 years. This Gryphaea shell connects to geologic time, genetic ancestry, landscapes, perseverance.

This time of the year during meditation I focus on growth, expansion, place, feeling based knowing, and collaboration with the more than human world. I am aware of how my body enters the space, what my feet, my back, my arms touch. I am aware of the sounds/light/smells/etc. Then, I simply ask, "what do you want to me to know." And, then I listen and breathe. Something remarkable usually comes through.

Drinking: Every chance I get, our large mason jar is outside brewing Sun Tea. I love making Sun Tea because, quite literally, the sky’s the limit. Any combination of favorite flavors can be placed together to make a refreshing treat. It couldn’t be more simple.

6 cups water

3 - 4 tablespoons loose tea

Place all ingredients in large mason jar with lid on. Let sit in sun for 4 or more hours. After time in the sun, strain loose tea from liquid. Return tea to jar and add honey to taste. Stir and chill.

Combinations we like:

Assam and sliced Lemon

Hibiscus flower, Lemon Balm, Lemon Verbena, and Peppermint leaf

Remember, as always, consult with a healthcare professional before trying any herbal preparations.

Listening: Mother Earth's Plantasia by Mort Garson, 1976, electronic. Subtitled “Warm earth music for plants…and the people that love them.” From his website:

“Well before Brian Eno did it, Garson was making discreet music, both the man and his music as inconspicuous as a Chlorophytum comosum. Julliard-educated and active as a session player in the post-war era…But as his daughter Day Darmet recalls: ‘When my dad found the synthesizer, he realized he didn’t want to do pop music anymore.’

“‘My mom had a lot of plants,’ Darmet says. ‘She didn’t believe in organized religion, she believed the earth was the best thing in the whole world. Whatever created us was incredible.’ And she also knew when her husband had a good song, shouting from another room when she heard him humming…Novel as it might seem, Plantasia is simply full of good tunes.”

Making: My super easy Summer Body Scrub recipe.

3 oz (84 grams) sea salt

1 ounce (30 ml) jojoba oil or olive oil

Fresh Rosemary sprigs, roughly chopped

I like to add 6 drops of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) essential oil as well to nourish the skin. Plus, I just love the aroma created between lavender and rosemary.

Mix all in a 4 ounce jar with a tight lid. Use one tablespoon at a time to scrub hands, arms, feet, legs, chest, neck, back. I like to use it in the morning as the rosemary helps wake me up. It’s also great after a day in the garden.

Note: It is best to make a fresh batch every few weeks. As always, consult with a healthcare professional before trying any herbal preparations.

Practicing in Yoga: We are in a waxing moon phase right now. This is a time of heightened energy. Getting things done feels like a priority. When the moon is waxing its light is growing. It starts as a crescent, and then, more and more of the moon becomes visible over 14 days until it reaches fullness as the Full Strawberry Moon on June 11th.

We are also building up to the Summer Solstice, a time that marks the height of potential and abundance. Summer Solstice + the Waxing Moon means grounding yet awakening, flowing yet liberating, celebrating yet recognizing the slow, subtle slide back to the dark. My practice right now, looks like this:

Thanks for reading A Crunchy Life’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

If you enjoyed this post, please feel free to share it. Your recommendation is what brings new readers to this little corner of Substack.